Every prisoner is quoted in his own words, however all last names have been omitted to shield the privacy and security of each.

It’s been 173 Christmas Eves since Scrooge shooed from his office two gentlemen seeking charitable contributions for the poor and destitute, dismissing their request with a pointed question, “Are there no prisons?” Indeed, Scrooge was told, there were, in fact, plenty of prisons. Plenty of prisons then, and plenty of prisons now. America has more prisons than any country in the world, which is why millions of Americans will spend December 25, 2016, in one of more than 6,000 correctional facilities.

In our society, what began as a religious holiday has morphed into a ubiquitous season. What happens when Christmas is stripped of all the extra poundage it has put on through the years―when it’s down to the barest of bones? To find out, I visited maximum-, medium-, and minimum-security Indiana prisons and asked men who live there to describe what it is like to be behind bars at Christmastime.

Common threads that emerged from these interviews include intensified feelings of loneliness, isolation, and despair. As Richard, serving six years for check fraud, put it, “There’s a lot of grief involved.” Thomas, whose two decades of incarceration include 15 years at maximum-security Indiana State Prison, said, “I feel lost. We’re in another world here.” Nick, serving 14 years for unlawful possession by a violent felon, observed, “Staff are on vacation more, so we have more lockdowns. Stress is higher with more arguments over long lines to use the phone.” Dwayne has been locked up for 18 years, serving a 76-year sentence for robbery with bodily harm. Dwayne told me, “It’s not as loving as it was when I was homeless. I loved when Christmas came around because I got to share the love at the shelters. What I miss most is helping others. And who I miss most is the homeless peoples.”

What was Christmas Past like for these prisoners?

Jason, serving eight years for forgery, told me that Christmas has always been his favorite holiday. His mother cooked feasts that included scalloped corn—“That was my favorite and she made it for me.” He loved shopping for gifts to stuff into everybody’s stockings, and bought useful presents like tennis shoes and clothes for a mother who often went without. The best gift he ever received was a 15 hands high Appaloosa named Rocky; a neighbor taught Jason how to ride and take care of the animal. “My nephew fed him apples; I was always scared the horse would accidentally bite his little fingers. But the best Christmas I ever had was when I volunteered for Coats for Kids. I was 28 and life was good. I was working with mentally handicapped people and I was doing well. On Christmas Day, I worked side-by-side with Santa Claus passing out coats. Seeing the kids’ faces light up—they were so happy—that’s the best thing I’ve ever done. I would love to go back and do it again.”

When you’re in prison, however, looking back is not recommended. David Leonard, Administrative Assistant 1 at Westville Correctional Facility, leans on 27 years of experience to explain why. “We make an investment in our offenders because we want them to go home. And so we teach them: Be patient. This is your reality. It’s up to you to make the best of it. We encourage them to participate in something and not to internalize the holiday.”

In fact, there are three main strategies for surviving Christmas in prison. One is doing what Leonard recommends: not internalizing. The second is faith. The most powerful is family.

Genaro, sentenced to 28 years for dealing in methamphetamine, helped me understand the first strategy. He told me he tries not to think about Christmas. He stays busy in an effort to trick him into thinking that it’s just another day. “I still care,” he says, “just not on that day. I don’t call home because I don’t want them to be thinking about me. I don’t want my mother to cry, and if I call on Christmas she will cry. So, I call the next day and ask her to tell me everything.”

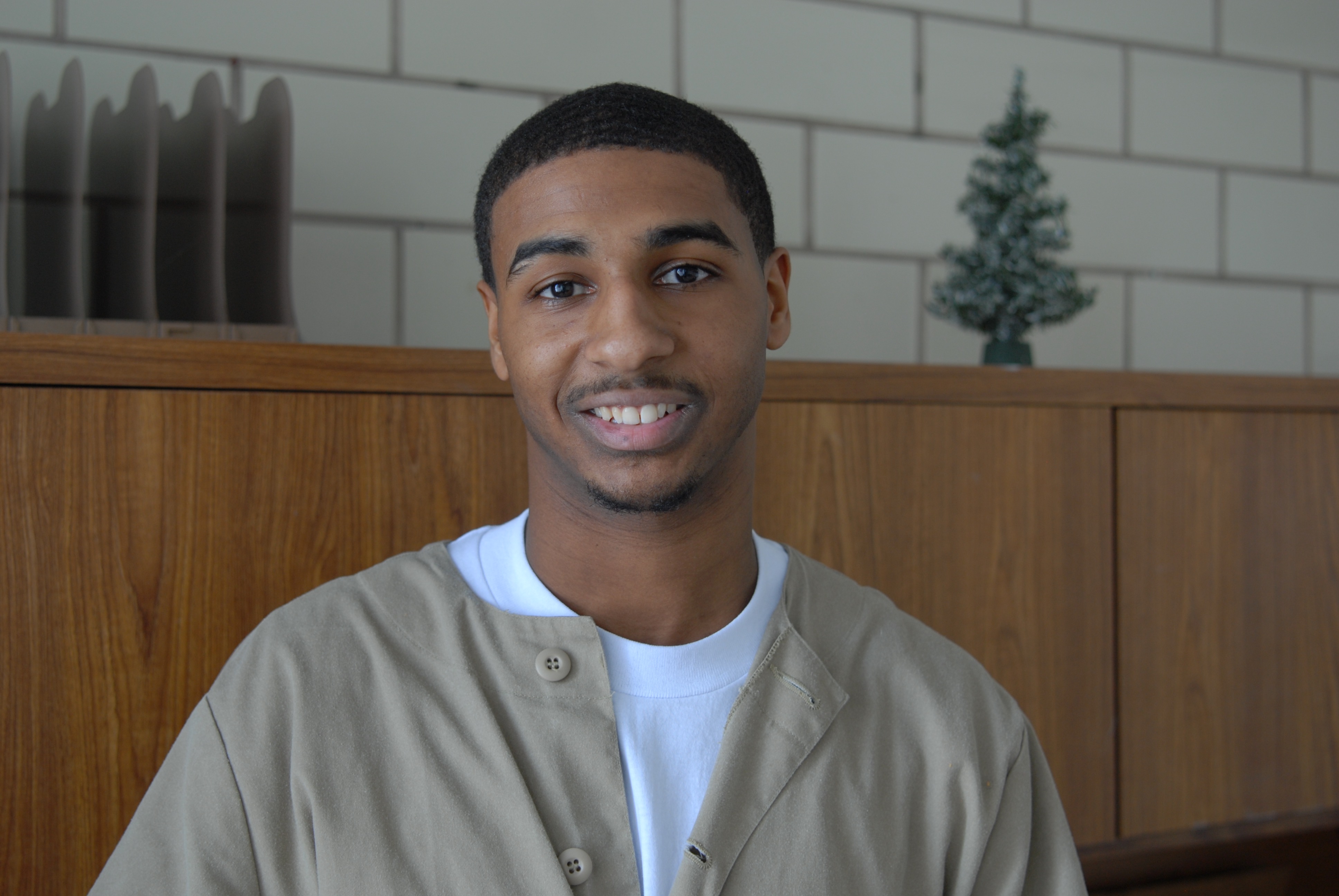

Joseph, 22, will also be relying on this coping mechanism to get through his third Christmas behind bars. For Joseph, it’s one day at a time, forget the past, work toward the future. Hopefully, Joseph’s conviction of battery and neglect will halt the generational cycle of abuse he experienced in his dysfunctional home.

Surrounded by family members who were addicted to alcohol and drugs, Joseph was subjected to physical abuse up to and including his teen years. Tired of the beatings and angry at the world, he remembers thinking, “I’ll just give up on me,” and dropped out of school. In 2014, Joseph became father to a son whose name and baby footprint are tattooed on his arm. One night when the baby was in his care, he blacked out on Zanax. He remembers nothing until the next day when he woke up in Marin County jail. At the age of 20, then, he was locked up and began the long journey to sobriety. Astonishingly, Joseph does not attempt to pass the buck by blaming his father. “It’s not his fault I became someone who was mouthy and wild when intoxicated.” Joseph is working hard to stay off cigarettes, hootch, and drugs and has been sober for one year and one month. He is counting on the skills he is learning in Westville Correctional Facility’s PLUS (Purposeful Living Units Serve) Program, a faith and character-based re-entry educational initiative, to help him break the cycle that derailed his life.

Without question, the PLUS Program is an essential piece of the prison puzzle. The study of six core values—honesty, respect, tolerance, responsibility, integrity, and compassion—are the heart and soul of this team-building approach to education. The youngest prisoner I met with, 19-year-old Eric, confessed, “Honestly, I didn’t even know what some of those words meant until I came here. The only word I had really heard was respect. But I think they can get you far away. My favorite one is honesty.”

Raised by a mother who is bipolar, Eric never knew what to expect at Christmas. “One year hopefully we got heat. Another year hopefully we got X Box.” At the age of 18, Eric was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to 30 years. “They waived me over as an adult,” he says, “trying to make an example out of me. I feel like since it was my first time in handcuffs it was too much. I feel like I should have gotten into trouble but I shouldn’t have gotten 30 years. I was still in high school.” His first Christmas in prison was the worst day in his life. “I couldn’t even talk to my mom.” Despite all of that, Eric shoulders responsibility, something he credits to the PLUS Program.

And yet, despite the wisdom of moving forward, others argue that there is value in looking back. Brandan provides a cogent example. Brandan was 18 and high on drugs when life as he knew it ended. Convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 35 years, this is Brandan’s sixth Christmas behind bars. Growing up in Gary, Indiana, Brandan noticed that tourists coming to see Michael Jackson’s birth home were too frightened of the environment to come outside their cars—“That’s what it’s like where I grew up.” When his mother was diagnosed with lupus and her food stamps were cut by ten dollars a month, Brandan wanted to help. He filled out applications for jobs but was not hired. He didn’t see any point in seeking help from anyone at Theodore Roosevelt High. “The 600 kids, principals, counselors, teachers―they’re all in the same predicament I am. I didn’t see anything else I could do to help my mother. The first time I go to rob someone…” Two weeks before Christmas Brandan killed somebody’s son, somebody’s husband, somebody’s father.

The first few Christmases in prison Brandan suffered being apart from his family. However, two years ago, “I put myself in other people’s shoes. That was the turning point when I didn’t think only of my family, I also thought of my victim’s family and what Christmas would be like for them. I’m mad at myself because it took this to open my eyes.”

When I asked the prisoners what sustains them, two words repeatedly rang like bell chimes: faith, and family. For the faithful, the birth of Jesus makes all the difference to their existence. Even in prison, Christmas is a time of joy and hope. Three testimonies in particular speak to this.

At 33, Pierre already has spent 14 years behind bars. “It’s been a long, rough journey through incarceration, but God opened my eyes and said ‘I’m taking back what is mine, and I don’t want you to regret one moment of your life because it brought you to where you are now.’ You know, the things that the world brings you are only a temporary fix. God is what is everlasting. You don’t need the things of the world for satisfaction if you have God.”

Robert, serving 20 years for armed robbery with two victim injuries, shared an astounding story of transformation. “Prior to this year I was Indiana’s second highest pagan minister. I had grown to hate Christmas—I saw it as a commercial sale—and I conducted a constant vendetta against Christians. I became so evil and disgusting that sickness had become cellular. I was a genuinely violent person. I had a conduct history of 100 write-ups, and 85 were violent. I was proud of that. I even set someone on fire in prison—he was a Christian. But something was changing in me. I got old I guess. Worn out. I was playing a role. I was homesick. I was scared. The person inside was crying out. One night my roommate talked to me about God and it hit me. Suddenly I felt the difference between dark and light. I felt like I’d been pulled out from under the water. I became the person I wanted to be with childlike love for people. I gave my life to Christ. There’s no greater feeling.”

Thomas, serving 9 years for operating a vehicle while under the influence and causing death, says that this is his first Christmas knowing Christ. I asked what it feels like, and he answered with a question. “When you were a little kid, did you ever go to bed when there was no snow and then when you woke up everything was blanketed in white? —Awe. Astonishment. That’s how I feel. I know that I am a part of this Christmas thing. It has nothing to do with gifts. It’s about love.”

While some prisoners distance themselves from the past, and many rely on faith in Jesus to make it through the holidays, virtually 100% of the inmates who shared their stories yearned for family. Looking over my interview notes, the word “family” appears on every page. Justin Rhymer, who is nearing the end of 10-year sentence for dealing in methamphetamine, has one wish: to be with his family. Richard wishes he could be with his wife. Thomas says, “I wish I could go home and be with my gramma, aunts, and uncle.” Jose dreams only of being with his wife and children. On and on it goes, every man longing for what was sacrificed when he committed his crime. Even Norman, who has served most of his 50-year sentence for murder, speaks of nothing but family. “Christmas,” he says, “is a time when I most miss being without my family.” And what about the man who lost his life so long ago? “I pray for his family all the time, but especially at Christmas. I pray that the Lord gives them peace.”

Perhaps nowhere is the experience of Christmas nostalgia and reminiscence expressed more evocatively than in Dylan Thomas’ 1954 classic, A Child’s Christmas in Wales. In it, the narrator explains what it is like to be a child at Christmas, inward and expectant: “But all that the children could hear was a ringing of bells. . . . I mean that the bells that the children could hear were inside them.”

Inside.

Prisoners know all about the inside.

And they yearn for what’s on the outside.

If there were such a thing as a magic wand, each and every prisoner I met would have used it to remove himself from inside and connect to loved ones on the outside.

It seems to me that the bell that rings inside the hearts of us all, young and old, believers and non-, free and incarcerated, is the memory bell of family. Even—perhaps especially―in prison, where there is so little to muddy it, the Christmas message is magnified. In prison, those who have almost nothing find inspiration in one holy infant whose birth refocused the world by shining a light upon the sacred bond that is family.